Return on Investment (ROI) Analysis of Exclusion Fencing

Written by Ellie Hays on August 20, 2025

In early May 2019, Central Tablelands Local Land Services (LLS) responded to a surge in wild dog attacks in the region by coordinating a tour for local sheep producers.

The group visited several properties in southern NSW to inspect various electric fencing systems being used for wild dog control. Through discussions with farmers and observations, it became clear that the Gallagher Westonfence electric fencing system was proving to be very effective at excluding wild dogs as well as foxes, feral pigs and deer.

The Gallagher Westonfence system is an electric exclusion fence designed for long-term durability and minimal maintenance.

It is available in two main forms: a vertical, traditional style for new fence installation or a retrofit style which uses sloping polyethylene droppers attached to an existing fence. Both styles are highly effective at reducing external grazing pressure and preventing predator incursions.

In the Central Tablelands, farmers were experiencing significant grazing pressure caused by external species and livestock losses due to wild dog predation. The Gallagher Westonfence system emerged as a highly effective solution, helping to protect while improving overall property management.

In 2019, Central Tablelands LLS launched the Feral Animal Exclusion Fence Grant Project, calling for expressions of interest from land managers. The program offered funding to successful applicants to support the installation of exclusion fencing. This approach reflects the growing recognition of exclusion fencing as a viable and effective tool for managing wild dogs.

In 2024, Agrista Pty Ltd was engaged to carry out a return on investment (ROI) evaluation of the electric fences installed on two properties that participated in the program. The study highlighted the importance of wild dog management due to the significant economic, social and environmental impacts of wild dogs and other external species in Australia.

Wild dogs are estimated to cause $64-$111 million in annual losses through both predation and disease transmission. These impacts extend beyond the farm gate, contributing to mental health challenges for producers and threatening the viability of rural communities. Wild dogs also prey on native wildlife, including endangered species.

In New South Wales, landowners are legally responsible for wild dog control under the Biosecurity Act 2015, making proactive measures such as exclusion fencing essential.

Influence of electric fencing on grazing pressure.

Vertical fence.

Retrofit fence.

Ilford

Background and Context

A sheep farmer located approximately 50km southeast of Mudgee faced challenges related to external grazing pressure in conjunction with wild dog attacks. The region’s rolling hills and sandy terrain influence livestock farming conditions. Wild dogs were present, as well as external grazing pressure, which led to significant pasture loss, with some paddocks stripped down to gravel. Colin and Eva installed 5km of vertical standalone fence which includes alternating electrified (hot) and non- electrified (cold) wires. As well as 5km of retrofit fencing.

Initially, Colin and Eva operated a 100% merino flock for wool production. However, to improve productivity, Colin transitioned to using Border Leicester rams over Merino ewes. This shift allowed the production of crossbred lambs that could reach 28-32 kilograms within 12 – 14 weeks. Despite this, excessive grazing pressure from external species resulted in vegetation loss and soil erosion, particularly in sandy areas.

Before the installation of exclusion fencing, high grazing competition contributed to limited pasture availability, reducing flock productivity.

Before fencing, maintaining flock numbers required Colin to purchase 200 replacement ewes annually. When replacement ewes became too expensive, a lower class-out percentage was used, impacting the breeding stock quality.

The first recorded wild dog sighting on the property was in February 2018, with activity increasing over time. Trapping efforts confirmed a significant wild dog presence, leading to a $7,000 investment in professional trapping services and a $45,000, 90-day control program. The combined grazing pressure from external species and the stress caused by wild dog activity placed significant strain on farm operations and the household. These challenges ultimately motivated Colin and Eva to invest in the Gallagher Westonfence electric fence.

To manage grazing pressure, 10km of exclusion fencing was installed around the boundary in 2019. As a fencing contractor, Colin completed the labour personally, reducing costs. For analysis, labour was valued at $12,000. The total material cost was $2,500 per kilometre, with an additional $2,000 spent on hiring a dozer to clear the fence lines. Where new fencing was constructed, the existing fencing was replaced with a 6-strand wire fence, incorporating electric wires on every second strand. The system operated via a continuous energiser unit, ensuring a consistent charge, with insulated posts maintaining efficiency.

The Gallagher Westonfence electric fence led to increased livestock survival rates, a rise in stocking capacity, and a 23% return on investment with a four- year payback period. Additional benefits included reduced labour for pest monitoring and improved pasture conditions, ultimately improving farm management and profitability.

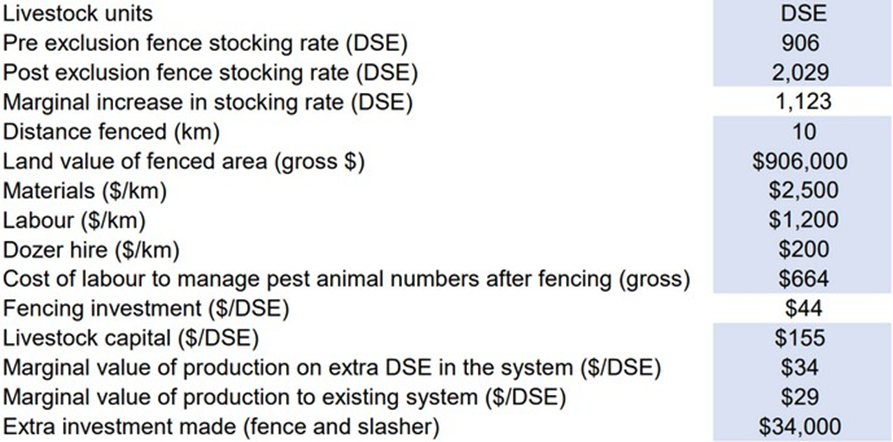

Investment Analysis

The exclusion fence was expected to increase stocking rates by improving pasture availability through reduced grazing competition and decreasing stock mortality by eliminating predators

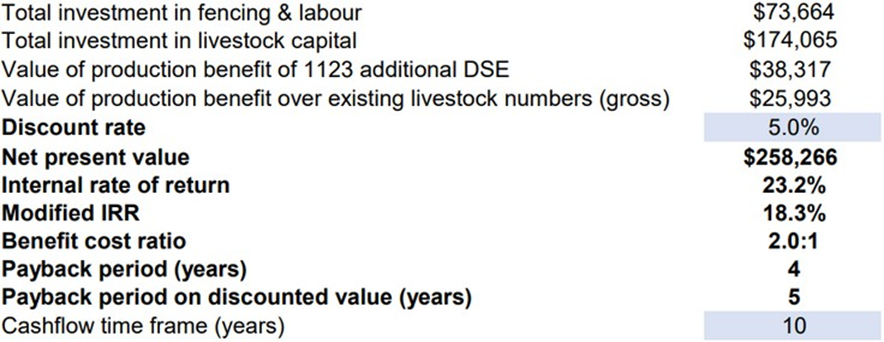

The total investment in fencing and labour was $73,664, while the livestock capital was $174,065, calculated based on additional DSE and industry benchmark costs ($155 per DSE).

To accurately compare the impact on livestock, the livestock numbers have been converted to Dry Sheep Equivalent (DSE). This provides a standard measure of pasture energy consumption between different classes and species of livestock. One DSE represents the energy needed to maintain a 50 kg castrated Merino wether, roughly 8.3 megajoules of metabolizable energy per day. The DSE rating varies based on factors like reproduction and class of livestock.

Production data before and after fencing was used to create two farm system models for comparison. Before the fence, the weaning percentage had declined to 60% for both adult and maiden ewes. By 2024, weaning rates increased to 130% for adult ewe and 110% for maiden ewes. Improved pasture availability also enabled a return to Merino wool production from a dual- purpose system. A proportion of the Merino wethers are now retained until 13 months, increasing wool sales. The analysis compared both systems using the same lamb prices and lambing months, with the primary variable being an increase in weaning percentage. Within two to three years, the stock increased from 906 DSE to 2,029 DSE.

Financially, the marginal operating profit per DSE was recorded at $34, meaning each additional livestock unit generated

$34 after covering costs. The total economic benefit, including improved weaning percentages, improved wool quality and reduced losses from predation, was $29 per DSE.

The return on investment was 23%, with a payback period of four years. Over a 10-year period, the benefit-cost ratio was 2.0:1, meaning every dollar spent generated $2 in returns.

Cumulative Cashflow and Financial Trends

The cumulative cashflow, shown in Figure 1, improved over time, with significant long- term financial gains projected over a 10-year period. Initially, the farm experienced a negative cashflow due to the upfront fencing, labour and livestock expansion costs. However, from Year 1 onwards, cashflow trends consistently improved. As shown in Figure 1 below, the break-even point was reached at four years over a 10-year period.

Figure 1 Cumulative Cashflow

Sensitivity Analysis

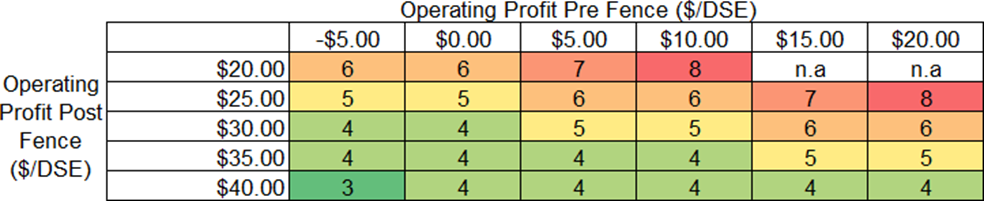

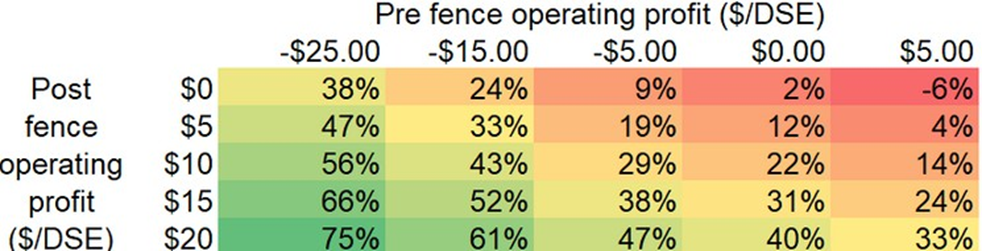

This sensitivity analysis evaluates how changes in pre and post-fence operating profit affect the payback period (measured in years) for an exclusion fencing investment. In this analysis, all other variables such as, total investment cost, increased livestock carrying capacity, and fence maintenance were held constant to focus solely on the impact of enterprise profitability.

The results show that as the post-fence operating profit increases compared to the pre-fence profit, the payback period shortens. Conversely, if there is little or no improvement in profitability, particularly where pre-fence profits were already strong, the payback period remains long or may not be achieved at all.

The heatmap in Table 1 illustrates these trends visually, with green areas representing a shorter payback period and red areas indicating a longer payback period. Overall, the analysis highlights that the economic success of exclusion fencing relies heavily on achieving a significant improvement in livestock enterprise profitability after fence installation.

Table 1 Sensitivity of the payback period (in years) pre and post fence operating profit.

Additional Benefits of Exclusion Fencing

Labour Savings

Colin and Eva significantly reduced their pest monitoring efforts following the installation of exclusion fencing. Before fencing, Colin spent a full day per week repairing damage caused by external species. After fencing, manual monitoring initially required one hour per day for the first three weeks but was then reduced to just one day per month for routine fence checks.

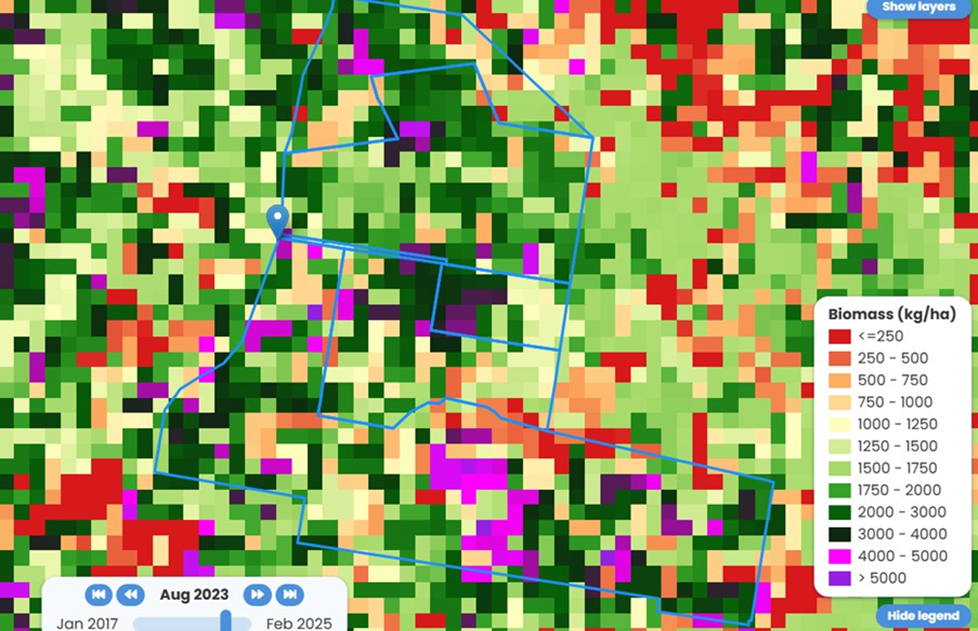

Cibo Lab’s Ground Cover and Biomass Comparison

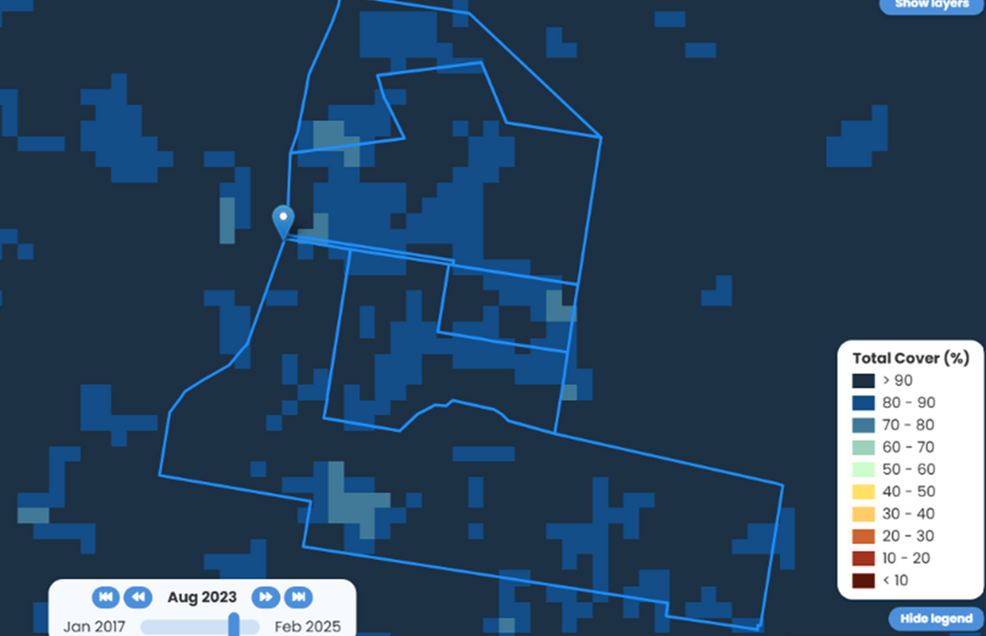

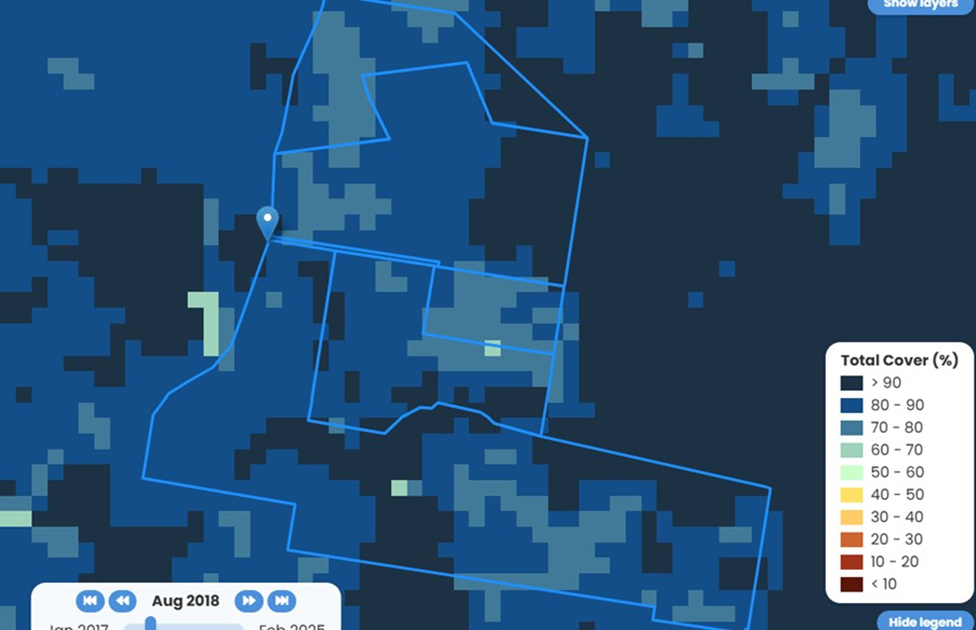

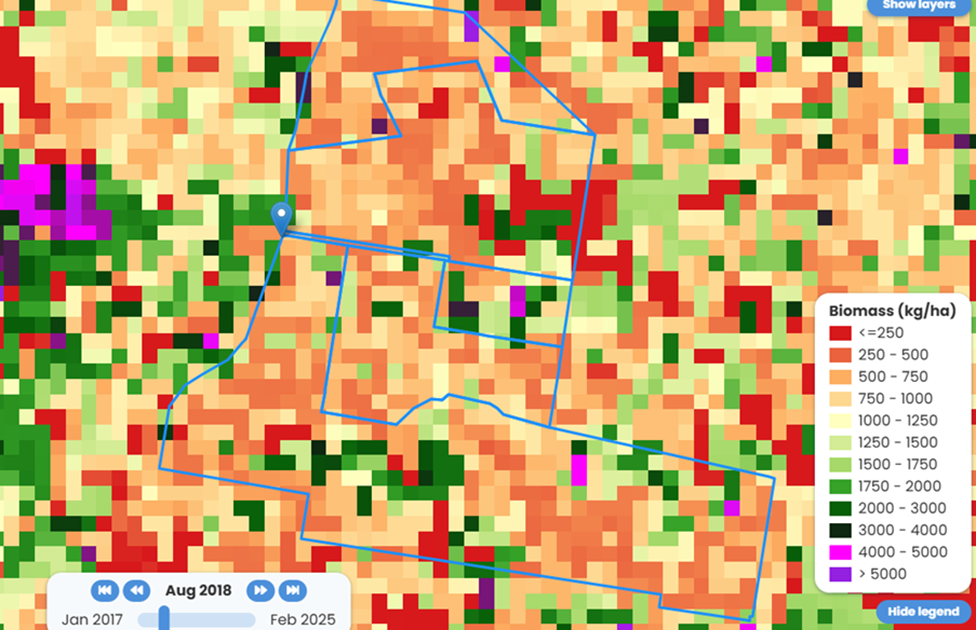

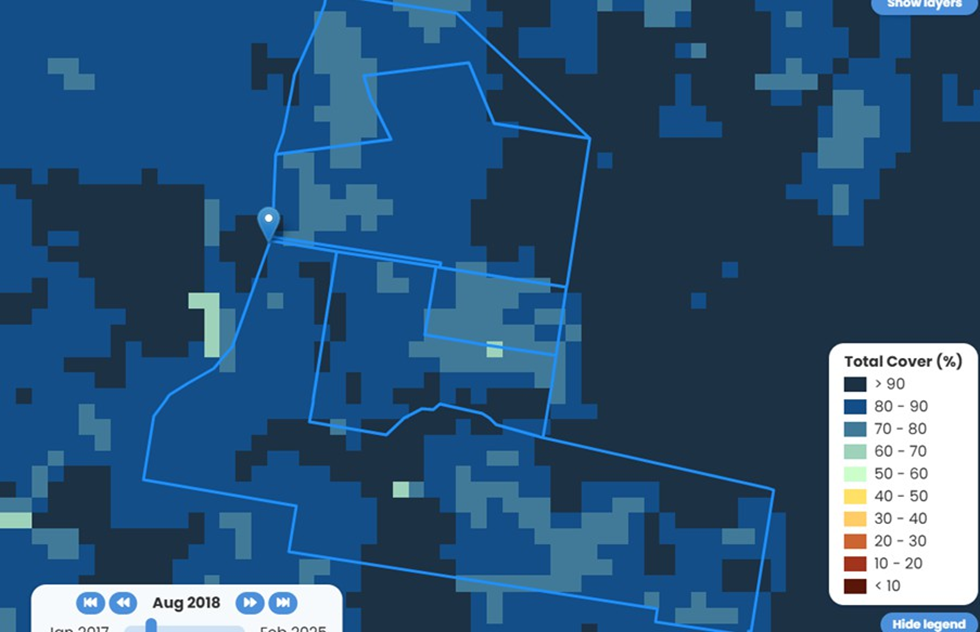

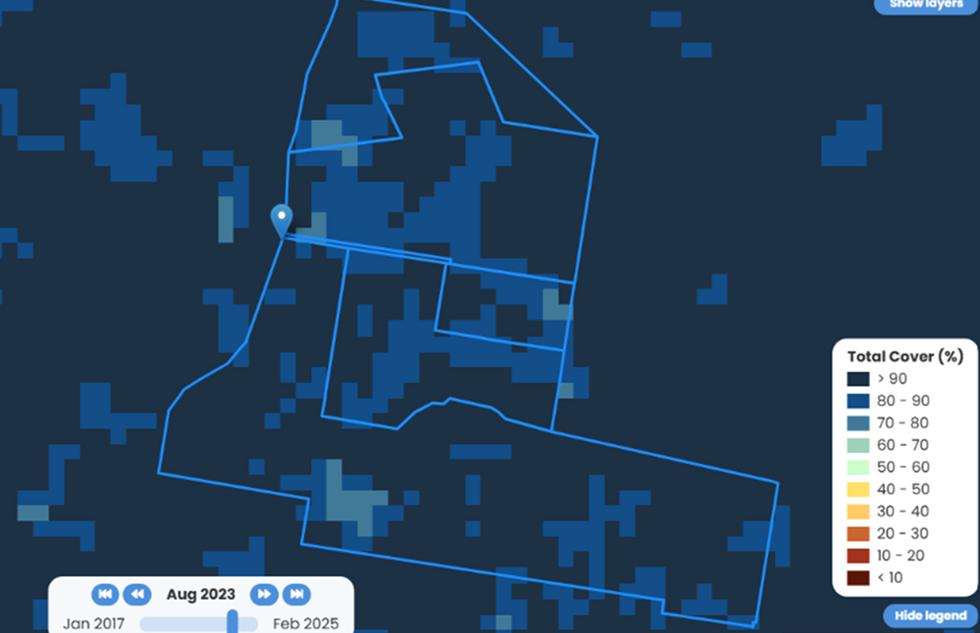

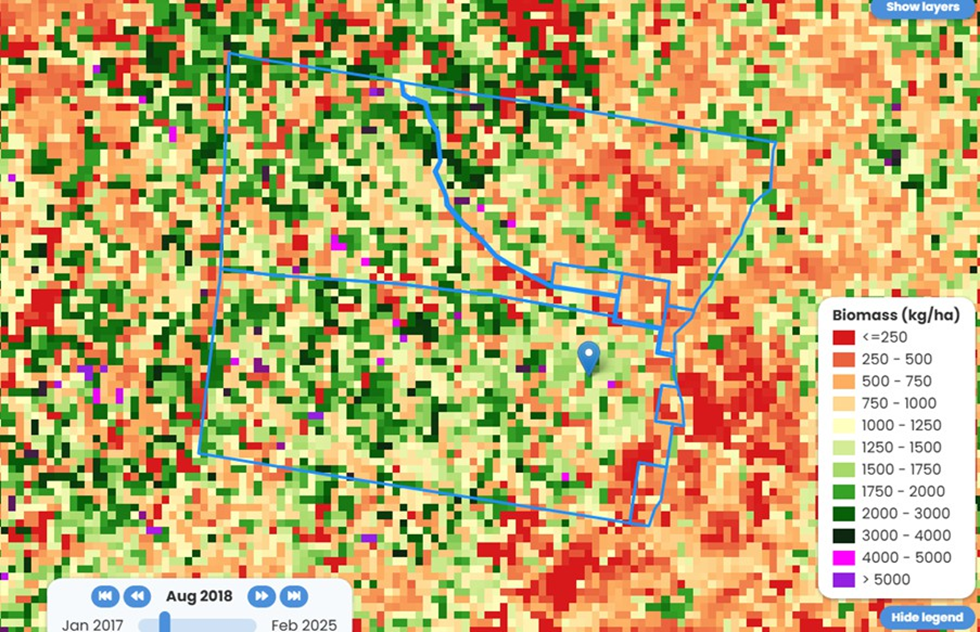

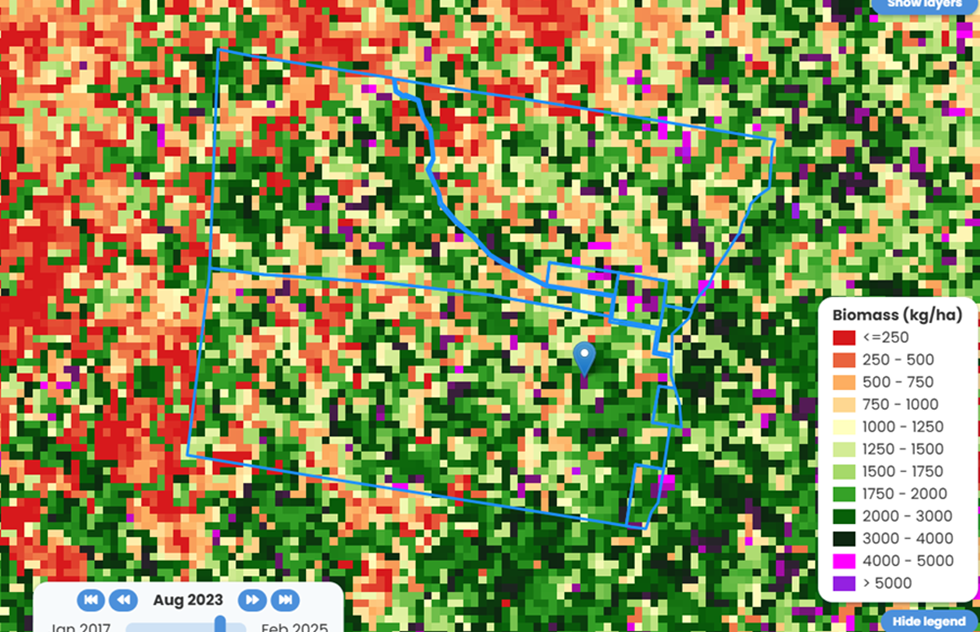

Data from Cibo Lab’ s Australian Feedbase Monitor tool (Appendix 1) showed an increase in pasture biomass and ground cover following fence installation. In August 2018, before fencing, the available pasture biomass was 1441kg DM/ha. This increased to 1735kg DM/ha by August 2023, indicating a 20% improvement. As annual rainfall was similar in comparable years, the improvement was attributed to reduced grazing pressure.

The increase in pasture growth allowed for diversification. Colin no longer needed to purchase replacement ewes and instead manages surplus feed by trading 70-80 heifers.

Additional internal fencing (4km) was installed to optimise pasture use. Increased ground cover also reduced erosion and washouts, enhancing the land’ s ability to respond to rainfall and support effective pasture growth. The images illustrate the feed availability on the farm after the exclusion fence was installed. The image on the right provides a comparison of feed availability between this farm and neighbouring properties, highlighting the significant increase in pasture biomass.

Conclusion

The installation of exclusion fencing reduced external grazing pressure and minimised livestock losses due to wild dogs. This resulted in improved flock health, increased lambing rates and enhanced pasture availability. The increase in available pasture biomass enabled greater stocking flexibility, eliminating the need to purchase replacement ewes and allowing for additional livestock trading opportunities. Labour efficiencies were also achieved, with significant reductions in time spent on fence maintenance and pest monitoring. These combined benefits contributed to improved farm management and long-term profitability, ensuring a more resilient and productive farming operation.

Appendix 1 Cibo Lab’s – Australian Feedbase Monitor

Turondale

Background and Context

Malcolm and Jodie, sheep farmers located approximately 100km south of Mudgee, faced challenges due to wild dog predation. Their farm, running approximately 10,000 DSE and set in hilly terrain with dense bushland and river valleys, receives an average annual rainfall of 640mm. For years, wild dogs had been a concern for their merino flock, but by 2013, occasional sightings turned into a persistent issue. By 2016, the impact was clear. In one mob of 820 ewes, only 16 lambs survived, whereas a similar age group near the house thrived with a 100% weaning rate. That year, six wild dogs were trapped confirming the extent of the issue.

Sheep farming was their primary livelihood, with their ewes producing high quality wool. However, repeated attacks from wild dogs led to stress related issues in their flock, forcing them to sell older ewes in March instead of January. Additionally, they lost the opportunity to sell surplus ewes due to losses, resulting in foregone revenue of approximately $100,000.

Daily monitoring of cameras and traps took three hours, and they engaged local trappers for two 14-day control programs in 2018 and 2020, each costing $7,000. The ongoing predation also restricted the use of working dogs with older, previously stressed ewes, complicating the operation. As the situation worsened, some advised them to consider selling the farm.

Struggling with ongoing losses and considering selling the farm, Malcolm and Jodie installed 20km of sloping retrofitted barrier attached to the existing fence. The sloping version is angled outward from the existing fence, making it harder for animals to climb or dig under. A solar-powered energizer provides 10,000 volts ensuring an effective deterrent. The goal was to reduce stress on their family and protect their ewes during lambing. Construction began in July 2019 and finished in June 2020.

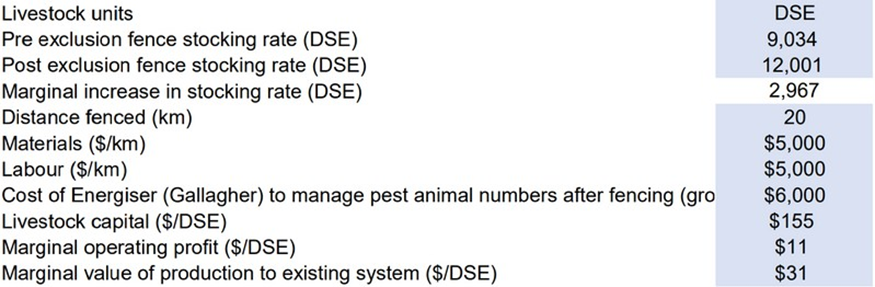

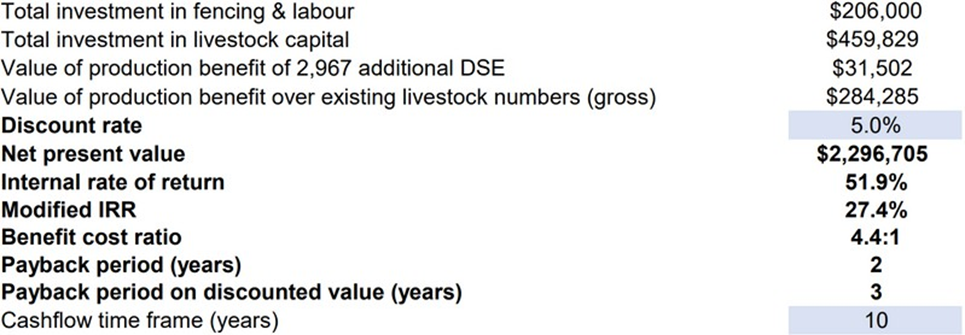

They enclosed the entire property with 20km of fencing at a cost of $10,000 per kilometre, including materials and labour. An energiser unit, costing $6,000, was essential to operate the fence. The Gallagher Westonfence operates by delivering a short, high voltage electric pulse when an animal makes contract, acting as a deterrent.

Following fence completion, a wild dog was sighted inside a lambing group in August 2020. The dog remained inside for 42 days, reducing the lambing percentage of that particular mob by 20%, highlighting the long-term effects of prior stress on ewes.However, overall, the stress and losses associated with wild dog predation decreased.

The Gallagher Westonfence electric fence led to increased livestock survival rates, a rise in stocking capacity, and a 51% return on investment with a two- year payback period. Additional benefits included reduced labour for pest monitoring, improved pasture conditions, and enhanced biosecurity, ultimately improving farm management and profitability.

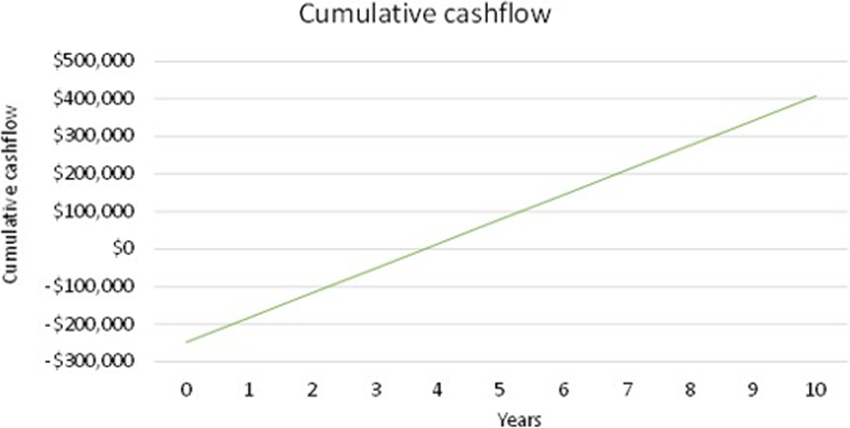

Investment Analysis

One of the biggest challenges Malcolm and Jodie faced was a drop in weaning rates, which fell from 90% to as low as 30% due to wild dogs. The exclusion fence was expected to improve stocking rates by reducing predator-related losses and stress. The total investment in fencing was $206,000, while livestock capital amounted to $459,829, calculated based on additional DSE and industry benchmark costs ($155 per DSE).

To accurately compare the impact on livestock, the livestock numbers have been converted to Dry Sheep Equivalent (DSE). This provides a standard measure of pasture energy consumption between different classes and species of livestock. One DSE represents the energy needed to maintain a 50kg castrated Merino wether, roughly 8.3 megajoules of metabolizable energy per day. The DSE rating varies based on factors like reproduction, growth targets, and livestock species.

To measure the impact of installing the fence, real financial and production data were used, adjusting for external factors like drought. Stocking rates and operating profit were compared over an average of two years before and after the fencing. Within two to three years, the stock increased from 9,034 DSE to 12,001 DSE, with cattle making up 25% of the farm’s operation post fence. The investment led to higher production, lower labour requirements and reduced pest control costs.

Financially, the marginal operating profit per DSE was $11, meaning each additional livestock unit generated $11 after covering costs. The total economic benefit, including higher weaning rates and improved wool quality, was $31 per DSE. The return on investment was 51%, with a payback period of two years. Over a 10-year period, the benefit-cost ratio was 4.4:1, meaning every dollar spent generated $4.40 in returns.

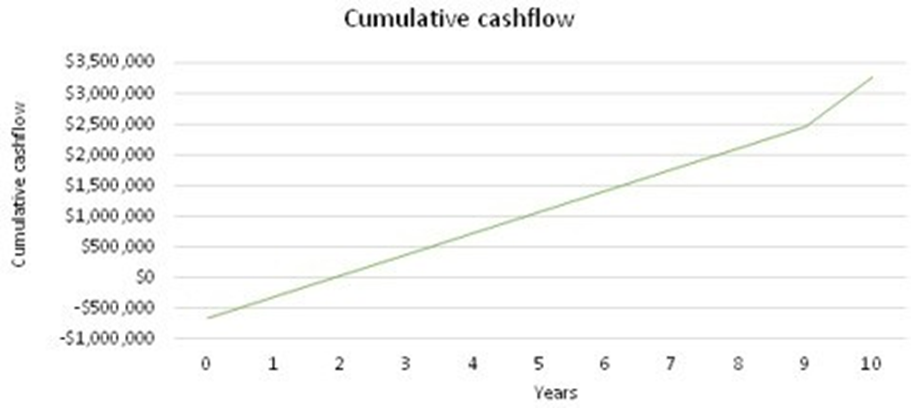

Cumulative Cashflow and Financial Trends

The cumulative cashflow, shown in Figure 1, improved over time, with significant long- term financial gains projected over a 10-year period. Initially, the farm experienced a negative cashflow due to the upfront fencing, labour and livestock expansion costs. However, from Year 1 onwards, cashflow trends consistently improved. As shown in Figure 1 below, the break-even point was reached at four years over a 10-year period.

Figure 1 Cumulative Cashflow

Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis evaluates changes in return on investment to differences in operating profit before and after erecting the fence. The results indicate that as post- fence operating profit increases, the return increases. The colour coded heatmap visually demonstrates this trend, with green areas representing greater returns and red areas indicating lower returns.

For the investment to be profitable, either an increase in net income or a significant reduction in costs is necessary. This can be achieved by increasing the operating profit per DSE, increasing the total number of DSEs in the system, and/or lowering expenses. Refer to Table 1 below.

Table 1 Where the gap between operating before and after fencing is over $40 returns exceed 60 percent.

Sensitivity analysis on IRR on pre and post fence operating profit.

Additional Benefits of Exclusion Fencing

Mental load reduction

Before the fence was in place, the mental and emotional toll on the family was immense. Despite their best efforts, they remained on constant alert, which affected their quality of life. Children, instead of playing, would spend time looking for dog tracks and setting traps, mirroring the family’ s ongoing vigilance. The decision to install the fence led to criticism from surrounding producers, who felt it shifted the responsibility onto others. This judgment, combined with sleepless nights due to concern for their livestock, created a heavy mental load. The lack of support from others added to the frustration. After the exclusion fence was in place, there was a noticeable improvement in sleep and mental well-being, illustrating the significant relief from the burden of constant stress.

Cibo Lab’s Ground Cover and Biomass Comparison

The implementation of an exclusion fence led to an increase in pasture biomass and higher total ground cover, as shown by Cibo Lab’ s data extracted from the Australian Feedbase Monitor tool, Appendix 2. In August 2018, before fence instalment, the average biomass was 1171kg DM/ha.

This increased to 1763kg DM/ha by August 2023, indicating a 50% increase. Notably, both years used in this biomass and ground cover comparison received similar annual rainfall, indicating that the increase was primarily due to reduced grazing pressure, which wasn’ t initially factored in when planning to install the fence. These results highlight exclusion fencing as an effective pasture management strategy.

Labour Savings

These farmers significantly reduced their pest monitoring efforts. After fencing, manual monitoring was virtually eliminated, requiring just one hour per week for any necessary repairs. Malcolm and Jodie reported they now have greater confidence in fence integrity, with sensors detecting issues like fallen trees, allowing for targeted repairs.

Biosecurity

Post-installation of the exclusion fence, there has been an increase in confidence regarding biosecurity, particularly due to the decreased presence of wild pigs. Exclusion fencing serves as a critical biosecurity measure by preventing wild animals from accessing farm areas, thereby significantly reducing the risk of disease transmission, thereby significantly reducing the risk of disease transmission.

Conclusion

The exclusion fence proved to be a transformative investment, delivering significant financial returns, reducing labour demands associated with pest control, and enhancing overall farm productivity. Beyond the economic benefits, it also alleviated the emotional strain on the family, allowing them to focus on future growth and long-term success.

With the wild dogs kept at bay, they could wean and sell older ewes in January when they have maintained a weight of 50kg. Their children were able to run 150 goats as a sideline business, something previously unthinkable. Instead of spending hours monitoring and managing pest threats, maintenance has been reduced to only an hour per week. The monitoring system now alerts them to any issues, improving the efficiency of fence checks. Given the difficult terrain, this system was essential for monitoring the back fence.

Appendix 2 Cibo Lab’s – Australian Feedbase Monitor

This article has been released with permission from the Central Tablelands, Local Land Services.