Beyond Chaos – The Power Of Perfect Lamb Systems

Written by John Francis on July 22, 2025

A self-replacing prime lamb enterprise is one of the most complex systems of the broadacre livestock enterprises. The complexity means that profitability is not linked to a single factor rather it is dependent on a range of factors each with their own impact on the bottom line and many with interdependencies on those other factors.

Industry-based prime lamb profitability solutions appear to ignore this complexity and instead offer simple, component-based solutions that lack an understanding of the interdependency of the relationships of the component on other parts of the system.

Examples of simple solutions to improving profitability without adequate consideration to the consequences include:

- high ewe lamb numbers as a proportion of total breeding numbers,

- high weaning percentages without consideration of the marginal investment in labour and supplementary feed or at the opportunity cost of stocking rate

- carrying lambs beyond the point of seasonal feed quality decline to deliver extra income but without consideration to the additional costs (shearing, animal health, labour and feed).

Renowned systems thinker, Russell Ackoff highlighted the limitations of improving systems through a component-based approach. He famously stated that a system is not the sum of the behaviour of its parts, but the product of their interactions. In other words, a system’s performance depends more on how its parts work together than on how well each part performs individually.

To illustrate this, Ackoff used the analogy of building a car using the best parts from different manufacturers—an engine from Ferrari, a transmission from Porsche, and a suspension from Rolls-Royce. While each component is top tier on its own, the resulting car wouldn’t function at all. Why? Because these parts weren’t designed to work together—they don’t fit.

This analogy delivers a critical insight: optimizing individual components in isolation does not guarantee an optimal system. True improvement comes from optimizing the system as a whole.

Following is a list of key measures that when achieved without compromise deliver solid financial returns in a prime lamb enterprise. It is the combination of all these performance measures together, rather than just a few in isolation, that deliver reasonable operating returns.

Prime lamb enterprise benchmarking data shows that it is possible to achieve solid financial performance in the absence of any one of these measures but failure to meet multiple key measures without compensation through additional production or reduced cost significantly increases the risk of financial underperformance.

These are strategic rather than tactical targets. Where feed supply has been constrained due to seasonal variability, many of these targets will be unattainable. In such cases, tactical management should be prioritised to optimise the financial outcome given the impact of the changes.

Strategic key performance measures to deliver high profit margins with good production levels in prime lamb enterprises.

- More than 1 ewe joined per hectare per 100 millimetres rainfall received.

- A target of less than $12 per DSE in sheep trading losses. Factors affecting this include the difference between ewe lamb value and the sale price of aged ewes, ewe mortality, ram purchase costs.

- An age structure with six lambing age groups with as few ewe lambs in the flock to remain self-replacing, apart from aged ewes no more than 8% annual losses as mortality and culls.

- Operating cost (enterprise plus overhead costs) of less than $45 per DSE or $115 per ewe joined inclusive of supplementary feed costs.

- Production of greater than 24 kilograms carcase weight per hectare per 100 millimetres. This equates to 155 kilograms carcase weight per hectare in a 650mm rainfall zone.

- Average daily gain of greater than 0.24 kilograms liveweight per head per day across all sale lambs. This will typically require most lamb sales within 180 days of birth and confines lamb energy demand to the growing season when the high-quality, low-cost feed is grown.

- Greater than 130% lambs weaned to ewes joined. Usually, this requires greater than 145% from adults and 85% from ewe lambs.

The system and its importance

The system is critical to achieving these targets. Considerations when designing a livestock production system include:

- the magnitude of feed supply by month

- the quality of feed supply by month

- the frequency and magnitude of the volatility in feed supply & quality by month

- the energy requirements of ewes during their different reproductive phases

- the impact of fertility on energy requirements

- the efficiency of conversion of pasture energy to weight (average daily gain)

- the number of days required to meet the minimum target market weight

- the requirements of the target market (e.g. weight, fat cover, wool length)

- the trade-off between price and timing of supply

It is impossible to be prescriptive about operational timings because seasonal growth differs by locality and the quality of the resource base. Time of lambing and time of turnoff are two important features of the prime lamb system. One of the challenges faced by the manager of a profitable prime lamb production system is the compromise between lambing time, which ideally occurs at the front end of the pasture growth season, and the time required to meet market specifications, occurring at the back end of the pasture growth season.

Analysis of profitable prime lamb production systems in south-eastern Australia suggest a profitable system is designed to optimise production of lamb carcase weight per hectare. The manager of such a system doesn’t aim to deliver the highest value per kilogram of lamb produced, rather they accept the commodity nature of their production system and produce enough kilograms per unit of pasture utilised to compensate for the probable lower price received due to higher supply at the point of sale.

The date of lambing in these systems is a delicate balance between:

- being late enough to have adequate feed of adequate quality to support the optimum number of ewes per hectare through a period of typically low feed supply and;

- being early enough to ensure there is an adequate number of days to sale to deliver enough carcase weight per unit area and per head without excessive cost.

The optimum number of ewes per hectare is dependent on the physical attributes of the resource base (soil depth, soil fertility, pasture quality, rainfall) but typically equates to greater than 1 ewe joined per hectare per 100 millimetres of rainfall assuming reasonable soil nutrition, pasture quality and rooting depth in medium to high rainfall zone.

As is demonstrated in the analysis of other livestock enterprises, there is more than one way to deliver the key performance measures. Some highly profitable lamb producers manage a high number of ewes per hectare and accept lighter lamb weight per head sold while others run fewer ewes per hectare with heavier lamb weight per head sold. Neither however compromise on carcase weight produced per hectare.

“Without excessive cost” refers to the genetics, animal health, pasture quality and management skill to deliver the majority of sale lambs to market before pasture quality declines. Lambing too early increases pressure on autumn–winter pastures due to the increased energy demands of lactation, increasing supplementary feed costs and risking fertility by pushing seasonal breeding limits.

Lambing too late risks low production due to insufficient days on high quality feed to meet the minimum target market weight specifications.

The consequences of low production are:

- low lamb sale weights per head and the associated discounted price per kilogram to reflect the high cost of weight gain for a store lamb buyer through the summer and autumn months.

- high retention rate of lambs beyond a desirable date of turnoff which comes at the opportunity cost of using the feed for an alternative lower cost animal.

- high cost of production due to insufficient production diluting the cost structure.

The consequences of lamb retention and the battle of influences

The consequence of the retention of lambs at optimum stocking rate beyond the desirable date of turnoff include:

- the compromise of the partitioning of already limited pasture energy reserved for the optimum number of ewes. This compromise is exhibited as the cost of additional supplementary feed, the cost of future reproduction due to inadequate energy supply to the ewe or the cost of future ewe numbers per hectare.

- the cost of additional lamb shearing and crutching to meet processor or trade buyer demands.

- the cost of additional animal health requirements to ensure growth isn’t compromised by internal or external parasites.

- the cost of labour necessary for the additional handling and feeding of the lambs

- the cost of additional complexity.

The livestock agent, who often has undue influence at or before this point of potential sale, has a significant undeclared conflict of interest (which rarely stops the provision of advice). The agent is incentivised by the income rather than the profit of the decision maker. This means that the agent receives earnings on any additional income irrespective of the extent of the net gain from the decision to carry lambs.

The lamb grower, on the other hand, incurs all the cost of carry including the additional cost of shearing, animal health, supplementary feed, labour and even increased selling costs. They also incur the risk of uncertainty of the future market movements, feed supply, feed quality and weight gain. This explains the divergence in emotion between parties from the exuberance of the agent to the apprehension of the grower when a decision is made to retain lambs later sale.

Where systems are stocked optimally, the retention of lambs beyond the optimally desirable sale date results in a compromise in pasture energy availability to ewes. The consequence of a system retaining lambs beyond the optimally desirable date is future production per hectare due to either lower reproductive rates or lower ewe numbers per hectare. These costs appear to be poorly understood by most managers and are identified only by the minority of astute managers who pay adequate attention to year-on-year prime lamb productivity performance indicators such as ewe numbers per hectare and energy consumption (DSE) per ewe joined.

The effect of deviating from key performance targets

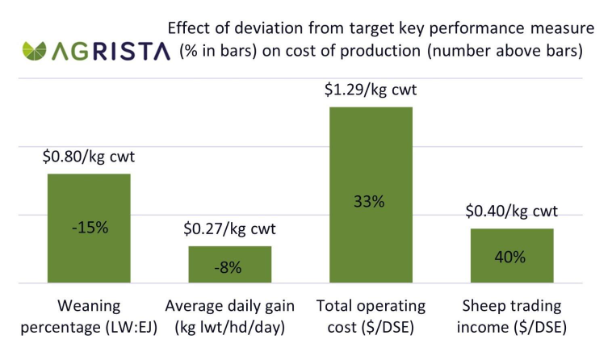

Figure 1 shows the extent of the variation in four performance measures between the average and target performance. Agrista farm benchmarking data has been used to show the difference in performance between the aggregated average titled “BM average” and the targets determined from the performance of a cohort of highly profitable prime lamb managers, titled “Target”.

Figure 1. The extent to which the average prime lamb enterprise deviates from the target varies for different performance measures.

Figure 2. shows the extent of the deviation between average and target performance shown in Figure 1 and the impact of this deviation on the cost of production. The percentage figures shown in each bar show the extent of the deviation of the average benchmarking performance from the target level of performance expressed as a relativity. The figure expressed in dollars per kilogram carcase weight above the bar relates the extent of the change in cost of production due to the deviation from target to average performance in the performance measure.

Figure 2. shows that there has been variation in the extent of the deviation between target levels of performance and those achieved by the average prime lamb enterprise manager. This data also shows that the cost of the deviation is not necessarily aligned to the extent of the deviation. For example, a 15% relative difference in weaning percentage delivers a change in cost of production of $0.80 per kilogram carcase weight while a 40 percent relative difference in sheep trading income (loss) relates to a $0.40 per kilogram carcase weight change.

Figure 2. The impact of the deviation from target levels differs depending on the performance measure and the extent of the deviation.

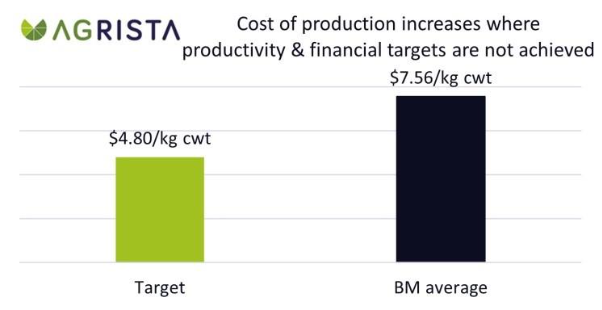

Figure 3. shows the cumulative effect of the deviation in multiple key performance measures between the benchmarking average and the target. The cumulative effect equates to $2.76 per kilogram carcase weight. The increase in cost of production is due the combination of the increased operating cost and the lower production in the benchmarking average when compared to the target.

The benchmarking average delivered lower production due to the lower weaning percentage. Assuming a price received of $8 per kilogram carcase weight and a scale of 1,000 hectares the value of the difference in delivering the target or the benchmarking average is over $400,000 in operating profit.

Figure 3. The cumulative impact of deviating from the target level in four key performance measures is $2.76 per kilogram carcase weight.

A highly profitable prime lamb system is only successfully achieved by a few disciplined producers who pay extreme attention to detail and understand that operational timeliness cannot be compromised. There are multiple factors driving success in this enterprise and most of them are dependent on each other to deliver a profitable outcome. This means that it is important not to consider a fix to the system based on an improvement to component in isolation. Each one of these components will have an inter dependent impact on some other part of the system and in many cases the dependency and effect is never clear.

I have spoken with many profitable prime lamb producers in the pursuit of simple solutions for others who are not delivering in this enterprise. I have not found them. Rather it appears that it is necessary to devote attention to detail to every component of the system for the entire production cycle. These producers focus intensely on production efficiency, have an anticipatory approach to decision making, prioritise operational timeliness and avoid compromises that others accept, often unaware of the extent of the value their disciplined approach delivers.

What this means for you

This paper demonstrates the importance of setting key financial and productivity targets and the cumulative effect of deviating from these targets. While the headlines are currently swamped with the news of lamb prices exceeding $10 per kilogram carcase weight, the disciplined minority remain undistracted from the more important measures of productivity. They know their targets and they know the cost of deviating.

Call to action

Just as pilots rely on instruments (altitude, speed, fuel and radar) to fly safely, the prime lamb enterprise manager needs key performance indicators to help deliver on business goals, drive efficiency and navigate uncertainty.

If you are a prime lamb producer and you don’t currently know the production or cost of production of your enterprise, now is the time to act.

Use the QR code below to start by assessing your prime lamb enterprise performance today. Or get in touch with us https://www.agrista.com.au/contact/